An inside glimpse of how a Biblical verse gets translated into Nawat… [2016 note: This piece was written in 2008. The translation of the New Testament into Nawat is now complete and work has begun on the translation from Hebrew of the Old Testament. Over the years the same general approach to translation has been maintained, as have our overarching principles, but there has been some revision of technical and methodological details, as is natural. The article has been revised and abridged slightly for the 2016 edition.]

Things are not what they used to be. Think of translating the Bible into a hitherto unwritten language, and many people probably visualise a lone missionary in a hut poring over a well-worn Bible and a few reference books, handwritten notes gathered over the years, a manual typewriter and possibly a battery-operated cassette recorder, mud and mosquitoes, sweat and perseverance. For what, twenty years? Thirty perhaps? A lifetime?

For better or worse, this romantic scene does not describe our Ne Bibliaj Tik Nawat project at all, whose headquarters, if it has any in a physical sense, are located in North Carolina, where the project’s organiser and director, Jan Morrow, currently lives. Meanwhile the project translator, Alan King, lives on another continent, Europe. They have lived in El Salvador and worked for years in close contact with the Pipils. That is where Jan and Alan met some years ago and established their working relationship founded on a common passion for the cause of the Nawat language.

Once upon a time their absence from the country might have made it very difficult, not to say impossible, to maintain contact with their former local associates, let alone pursue a joint project such as translating the Bible into the native language, but times have changed and the twenty-first century has created new possibilities which it is up to us to put to good use.

Thanks to modern communication, Jan and Alan remain in daily contact with each other. Contact with people in El Salvador depends on how often our associates there are able to get on-line. Ever newer tools such as Skype, Facebook or YouTube are fast becoming familiar to the whole world, and the Nawat language is no stranger to them either!

Now let’s talk about translating: what difference has the modern computer age made to the way in which the Nawat Bible is brought into being? Let’s find out…

Alan lives in a small apartment in the Basque town of Zarautz. The walls are lined with books in and on numerous languages. Alan is a linguist, as well as an experienced language teacher and translator. But most of what goes on in this translation laboratory happens on the computer screen.

Ne Bibliaj Tik Nawat: What are you translating at the moment, Alan?

Ne Bibliaj Tik Nawat: What are you translating at the moment, Alan?

Alan: Matthew 18. I’ve just done verse 6: “But whoso shall offend one of these little ones which believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea.”

NBTN: Matthew. That’s the first gospel…

Alan: But not “my” first gospel. First I translated Luke, and then Mark, so Matthew is my third, and I’ll do John last of the four. Matthew is going to be finished before Christmas, and John early in the New Year. That will mean we’ll be half-way through the New Testament. Pending revisions, that is.

NBTN: Can you show us some of your work?

Alan: Okay…

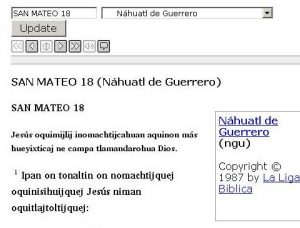

On the computer monitor was what looked like an impossible jumble of text windows of different shapes and sizes, some inside, on top of or underneath others. Three or four mouse-clicks later, a new Word document materialized filling most of the screen. It contained what looked like the book of Matthew in Nawat, quite nicely laid out and formatted. We scrolled down the 35-page document until we came to chapter 18. After verse 6 there was no more text, althought the remaining chapter and verse numbers were there.

NBTN: Okay, how did those Nawat Bible verses get there? Did you type this document?

Alan: No, the document you’re seeing just came into existence a minute ago. The computer generated it from text I type into another programme, which is where I actually do my translating and everything gets stored. It’s like a big data-base with a place in it for every verse in the Bible. The verses I haven’t translated yet just stand empty.

NBTN: In the document we’re looking at it just has the verse number and then “\vt” for each of the untranslated verses.

Alan: Yes, it’s just telling me that a verse text needs to go into each of those empty places. Now I’ll show you where the text I type in is kept.

Alan closed the Microsoft Word window. The earlier mass of little windows came back into view.

Alan closed the Microsoft Word window. The earlier mass of little windows came back into view.

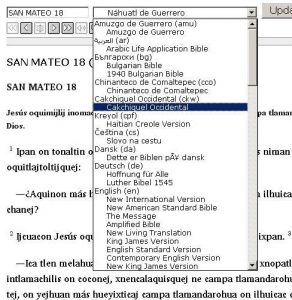

Alan: This is a very good programme developed by the Summer Institute of Linguists called Field Linguist’s Toolbox, but we call it just Toolbox. As well as the programme itself, the SIL people also provide a template for scripture translation projects that’s very useful, although I have modified and expanded it in some rather major ways for our project.

Now this window on the right-hand side here that says “NT40_MAT.txt” at the top is where the Nawat translation of Matthew goes. In these three windows to the left of that, I get to see the verse, while I’m translating it, in the original Greek and in two important translations, the Latin Vulgate and the English King James Version. When I’m working on the Old Testament I think I will want to have four versions in view: the original Hebrew of course, the Septuagint, the Vulgate and the KJV!

NBTN: Very nice…

Alan: What’s even nicer, and this is where the benefits of this programme come into play, is that through something called parallel movement, whatever verse I look at in one language, or am typing in in the case of the Nawat, the other windows automatically show me the same verse.

Okay now look at the window at the bottom that stretches from left to right: here in the left-hand column you see chapter-and-verse numbers, and the other columns show key terms occurring in any given verse in Greek, Nawat and English. They can be a help when translating and trying to remember what Nawat term I’m using for a given concept in Greek.

NBTN: Fantastic, but who put that information in there?

Alan: I did myself, apart from the groundwork contained in SIL’s scripture template. There are some other lists for key names, key numbers and key phrases that work in the same way. They all display the terms for the verse I’m working on automatically.

NBTN: So as you’re working through the texts and translating you decide on how to translate a term, a name or a phrase and enter them onto these tables, and when they occur again in another verse they “remember”, so to speak, and remind you what words to use?

Alan: Yes, that’s the basic idea. It works as a book-keeping system that helps me keep track of my previous decisions. That means I can save time when I next encounter the same word or phrase and also be more consistent.

NBTN: Sounds brilliant.

Alan: It is, and it gives good results. I can’t take any credit for the overall idea, that goes to the Toolbox people at SIL. What I’ve done is build on the foundation they provide and adapt it to the needs I have encountered. It’s a virtue of their system that it’s flexible and open enough to let you do that, of course. This is one of the benefits of this system.

Then there’s this other little window here that’s titled “KeyNTpp.txt”: “pp” is for parallel passages. This is another of those windows that “follows me around” and this one displays the references to other passages with similar content, some of which of course I will already have translated, so I can look at those and compare, and keep the parallel passages consistent with each other in translation.

NBTN: What if you don’t understand the Greek text? Surely that happens sometimes; it’s hard enough to understand the English translation of verses sometimes! I know you’ve got the Latin and the English there to help you, but say you need more information? Do you use reference books?

NBTN: What if you don’t understand the Greek text? Surely that happens sometimes; it’s hard enough to understand the English translation of verses sometimes! I know you’ve got the Latin and the English there to help you, but say you need more information? Do you use reference books?

Alan: I do have a number of books that can be consulted. But between what’s on the computer and on-line resources, the printed books are not always needeed these days.

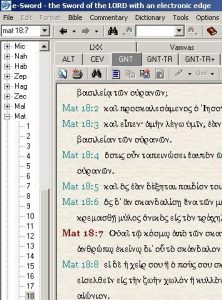

So here let me show you a programme called e-Sword, which is kindly provided for download free of charge via the Internet by another organisation. It’s a database full of a variety of Bible texts.

NBTN: How do you use it?

Alan: E-Sword consists of three main sections. There’s the Bible section where any part of the Bible can be viewed in any of a wide range of languages and versions; at the moment we’re seeing the Greek text. Notice the tabs along the top to switch to another Bible version with a single click. The index on the left-hand edge lets me choose any book and chapter quickly, or else I can just type what I’m looking for in the little window in the top left corner and it goes find it.

Second, over here on the right of the screen is the commentary section, where I can read a commentary on any verse I’m interested in, and see if that gives me some help understanding the meaning. There are several commentaries available for download, and I choose which one to read at any given time by clicking on the tabs at the top there. Since these materials are distributed free of charge, they are things that are no longer under copyright and hence taken from older books. If I want new books I have to go out and buy those. That’s one reason why I still need a library!

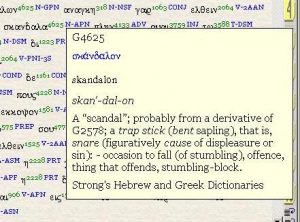

Back to e-Sword, at the bottom is the dictionary section. At the moment I’m using it to look at a dictionary entry for the word “skandalon”. It is keyed to what are known as Strong’s Numbers, which come from the most famous Bible concordance, where every Greek and Hebrew word in the Bible has its own number. And that correlates with a version of the Greek, Hebrew or English text that is tagged with the Strong’s Numbers too.

Back to e-Sword, at the bottom is the dictionary section. At the moment I’m using it to look at a dictionary entry for the word “skandalon”. It is keyed to what are known as Strong’s Numbers, which come from the most famous Bible concordance, where every Greek and Hebrew word in the Bible has its own number. And that correlates with a version of the Greek, Hebrew or English text that is tagged with the Strong’s Numbers too.

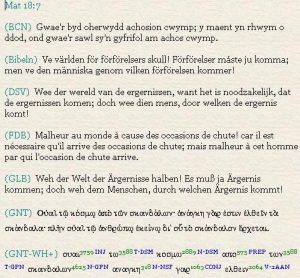

NBTN: What happens when you want to compare different translations of a given verse?

NBTN: What happens when you want to compare different translations of a given verse?

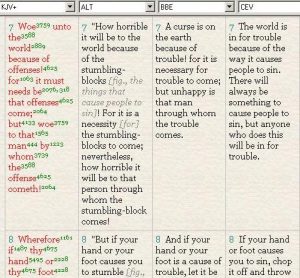

Alan: I click on the “Parallel” tab and get a display in parallel columns of the same verses in different versions. I like to have fairly different versions here in the same language (English). That way I can quickly get a feeling for some of the different approaches that have been taken to rendering (and sometimes even understanding!) a given verse.

Then I have another tab that says “Compare”. I like to use that one to compare a number of translations of a troublesome verse into different languages. I sometimes use that to focus on a specific word or phrase that seems to have more than one possible solution, to see which solution was taken by the translators into different languages.

Of course there wouldn’t be time in a lifetime to study thorougly everything in ever single translation, and it would be a bit useless too because a lot of information is ultimately going to be redundant because people have simply done the same things, often owing to a common source.

For instance: the Vulgate was very influential for the classical translations into European languages, and from there its influence extended further afield when European translations were taken as the basis for translations into other langauges. So unanimous coincidences in a long list of translations may not tell me much more really than I could have got just from reading the Vulgate, for example. All the same, it’s nice to have the resource of quick comparison between a number of languages.

For instance: the Vulgate was very influential for the classical translations into European languages, and from there its influence extended further afield when European translations were taken as the basis for translations into other langauges. So unanimous coincidences in a long list of translations may not tell me much more really than I could have got just from reading the Vulgate, for example. All the same, it’s nice to have the resource of quick comparison between a number of languages.

NBTN: How big is the complete set of e-Sword Bibles? Iis it possible to include all the Bibles you’d ever want to look at in the e-Sword application?

Alan: No. It isn’t that complete!

NBTN: What do you do about the other versions you need to consult?

NBTN: What do you do about the other versions you need to consult?

Alan: I can use other packages. Read them on the Internet. Or get the book… It depends on what’s available in each case. Since I’m translating into an American Indian language, it is sometimes useful to be able to compare how things are dealt with in Bible translations into other indigenous American languages. For example there is a Bible in one form of Nahuatl on BibleGateway.

NBTN: This is a website offering a number of versions of the Bible?

Alan: Yes, one of several. But the whole thing isn’t downloadable as a programme like e-Sword, so an internet connection is required, and it doesn’t have e-Sword’s sophisticated features such as verse-by-verse parallel movement, commentaries or dictionary support. Casual readers would probably find it more practical though. It is very good for simple reading or browsing, whereas e-Sword is more of an intensive research tool, so they’re both good in different ways. But the best of all worlds is to have both!

NBTN: So you have access to a much wider range of translations than an old-fashioned Bible translator in his or her proverbial grass hut could have dreamt of. But there are still only twenty-four hours in the day: are there certain Bibles that you tend to pick up, virtually or physically, more than others in the course of an average day’s translation work? Which are your favourites?

Alan: Apart from the original source texts, there are the Vulgate and the King James, and some of the other English ones for contrast, and a selection of European translations to fill out the picture as I also mentioned… Here’s one I open from time to time when I’m short of ideas: the New Testament in Hawaiian Pidgin. Let’s look up Matthew 18:7, the verse we’ve just been looking at in various versions and languages… here it is: “Auwe! Da peopo hea inside da world, dey goin get it! Cuz get guys ova hea who try fo make odda guys do bad kine stuff! Fo shua, goin get peopo dat like make odda guys do bad kine stuff. But auwe! Da guy dat make one nodda guy do bad kine stuff, he goin get it!”

Alan: Apart from the original source texts, there are the Vulgate and the King James, and some of the other English ones for contrast, and a selection of European translations to fill out the picture as I also mentioned… Here’s one I open from time to time when I’m short of ideas: the New Testament in Hawaiian Pidgin. Let’s look up Matthew 18:7, the verse we’ve just been looking at in various versions and languages… here it is: “Auwe! Da peopo hea inside da world, dey goin get it! Cuz get guys ova hea who try fo make odda guys do bad kine stuff! Fo shua, goin get peopo dat like make odda guys do bad kine stuff. But auwe! Da guy dat make one nodda guy do bad kine stuff, he goin get it!”

NBTN: What about Spanish translations?

Alan: I have access to several of them in one form or another, and at first I expected to be using them quite a lot, but to be quite honest, all the ones I’ve seen are quite conservative and so generally fall in line with standard European translations in other languages which all follow each other quite closely. The Spanish translations tend to stay close to the Latin (even thought that is not the original language of the Bible). That doesn’t necessarily make them bad translations, but they hardly ever tell me anything I don’t already know.

NBTN: How long do you spend translating a particular verse, including comparison with other translations, reading commentaries, studying the meaning of specific words and so on?

Alan: As long as is necessary! That could be anything between less than a minute and more than an hour; it all depends. If I have a problem I will take as long as I have to in order to consider it carefully, read up on the verse or the word or both, consult translations, and so on. Experience has taught me that there is always a solution to be found. Sometimes that solution is immediately obvious, sometimes you have to dig for it. When there is spadework to be done, I do it; simple as that.

NBTN: Are you a perfectionist?

Alan: For better or worse I’m afraid I am, but maybe it is good to be one for some kinds of job. But you know, perfectionism in a good sense is not just taking as long as necessary to do something, it is also searching for ways to be more efficient so that you can achieve better results in less time, and thus cover more ground in a given period without sacrificing quality. I believe in efficiency and am all for using technology to help achieve it. What I am not for is wholesale adoption of technology to get “more” done more cheaply but not as well, lowering ones’s standards, abandoning our professional principles to embrace superficiality and slovenliness. I believe in quality over quantity. If that is being a perfectionist, fine. I have the impression Jesus was one too: “For many are called, but few are chosen”, “one jot or one tittle”…

NBTN: But that’s only half the story, isn’t it. How do you decide on the Nawat translation? Finding the right words must be a challenge. Is there a Nawat dictionary?

Alan: Not really. Luckily a fair amount of preliminary work on the language was performed by scholars during the twentieth century.

As a newcomer to the field my first task was to become thoroughly familiar with the existing literature and find out what else was currently being done (which turned out not to be much, sadly). Besides compiling information from existing vocabularies, the other chief way to make up for the lack of a dictionary is by collecting a corpus of oral or written texts and extracting as much lexical and grammatical information as possible therefrom. I started work on both of these fundamental tasks early on in my work on Nawat because I knew they were needed for further progress to be made.

As a newcomer to the field my first task was to become thoroughly familiar with the existing literature and find out what else was currently being done (which turned out not to be much, sadly). Besides compiling information from existing vocabularies, the other chief way to make up for the lack of a dictionary is by collecting a corpus of oral or written texts and extracting as much lexical and grammatical information as possible therefrom. I started work on both of these fundamental tasks early on in my work on Nawat because I knew they were needed for further progress to be made.

This linguistic groundwork is prior to and stands outside the Bible translation project yet is a necessary prerequisite for it. My work in that respect was in coordination with IRIN, the Nawat language recovery initiative, which I and several other key players started, some of whom were native Nawat speakers and others dedicated sympathisers.

I’d like to make three poionts here:

First, there is hardly any point translating the Bible into a language like Nawat unless some sort of language recovery process exists, enjoys the support and participation of the language’s speakers, and is actually doing things to keep the language alive.

Second, basic linguistic groundwork needs to be done to document the language for recovery purposes, i.e. to support teaching of the language and using it. These two things — recovery and documentation — need to progress hand-in-hand for either to be fully effective.

My third point is that recovery and documentation activities both need some sort of organisational structure and that such a structure ought to be autonomous and focused on these goals alone, run democratically with maximum indigenous involvement, and pervaded by an overriding sense of grassroots empowerment and teamwork.

NBTN: What is the connection between IRIN and Ne Bibliaj Tik Nawat?

Alan: They are mutually independent, and I think this is the correct relationship. Having said that, apart from the fact that they happen to share at least one member, I think it is also fair to say that they both share an essential goal in the wish to support Nawat language recovery and goodwill to cooperate and coordinate with each other. I hope we will be seeing examples of that in the months and years ahead. But of course the other “connection” is the point I’m making here, namely that the Bible project rests on the achievements of IRIN in language recovery work generally and documentation in particular. And that includes the lexical and corpus work that I started to tell you about.

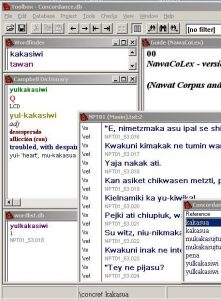

In my first few years working on Nawat I started two data-base-type sub-projects. One, called NawatLex, aimed to collect and systematise the information in existing Nawat vocabularies. The other was the Nawat text corpus, in which I began to collect Nawat language texts of all types. NawatLex was originally integrated into a data-base structure built using the Microsoft Office application Access. The corpus was transcribed into the current spelling we are using so as to be more readily searchable using concordancing software stored digitally as plain text. Although I say “I”, others helped at some stages and it may be considered a product of teamwork. Besides, I believe that the moral owners of this information are the language’s speakers, whatever efforts others make to systematise, digitalise and integrate it into modern technology.

NBTN: So to return to the present Bible translation process, you’re saying that we haven’t got a good Nawat dictionary (yet), however thanks to earlier efforts and IRIN’s groundwork we do now have the elements out of which a dictionary can and hopefully will eventually emerge? If we can focus on the actual mechanics of your work, in what form do you access that information in the “translation laboratory”?

Alan: Well, in line with evolving technology, IRIN’s Nawat corpus and NawatLex, although still under construction, are now being restructured and merged into a single big data package which incorporates both texts and lexical material. This has been baptised NawaCoLex (i.e. NAWAt COrpus and LEXicon). The building of NawaCoLex is still incomplete owing to the lack of funding for more intensive development, but in the first stage the most important and useful corpus and lexical components have been selected for adaptation to the new format.

NBTN: So the 2008 version of NawaCoLex is the main Nawat language data package used at present within the Bible translation process. What is NawaCoLex’s format?

Alan: Toolbox again. It was realised that Toolbox is a single type of framework that is ideal for housing both the lexical data and the Nawat corpus too. A further breakthrough was our realisation of the feasibility and benefits of housing both lexical and corpus components together in a common Toolbox “shell” and cross-referencing all the material simultaneously. It probably sounds complicated, and I would have thought it was myself until I saw how Toolbox makes it so easy that it started seeming increasingly silly not to go ahead and do that. And NawaCoLex is the result.

NBTN: So that gives you a dictionary and a corpus of texts sharing a single programme and cross-referenced.

Alan: Not just one dictionary but several dictionaries, indeed as many as we wish can be added. And here’s the beauty of it: when I look up a word, as I will in a minute, the system takes it for granted that I want it to look the word up in all its dictionaries. No need to check them one at a time. If it turns out the word only appears in one of the dictionaries, that dictionary entry displays and that is that. But if my word (or search string) is found in more than one dictionary, or in more than one entry within the same dictionary, a list is first presented to let me choose which dictionary entry to display.

NBTN: So you could put every Nawat vocabulary that’s ever existed into NawaCoLex and you’d never have to look up an item more than once to get an overview of everything there is for it?

Alan: That’s the general idea. The dictionaries reside in NawaCoLex as separate documents; the compilation of all the available information for items is done by the system and the user at look-up time. I’m afraid I didn’t envisage that as a viable option when designing its predecessor, NawatLex. I was still thinking in the more rigid terms of a single “flat” data set with a fixed number of fields per record, and so I thought it was going to be necessary to encode all the data from various sources into a single uniform mould: a long drawn-out preliminary process which for all intents and purposes merely gives the same result we’re getting now. Even what we managed to get done of NawatLex itself has been integrated into the NawaCoLex system as just one more dictionary, and its results also come up when doing searches.

Here’s an example (click on the image to see the full screen display), we’re looking at a search for the English word “trouble”, using the Concordance Lookup window at the top right. Although it’s called concordance, we’re actually “concordancing” the dictionaries right now, not the text corpus (though we can do that too!). That lookup specification brings up the Concordance window you can see at the bottom here, which has listed the seven dictionary entries it has found in which “trouble” is or forms part of the entry’s English gloss.

Here’s an example (click on the image to see the full screen display), we’re looking at a search for the English word “trouble”, using the Concordance Lookup window at the top right. Although it’s called concordance, we’re actually “concordancing” the dictionaries right now, not the text corpus (though we can do that too!). That lookup specification brings up the Concordance window you can see at the bottom here, which has listed the seven dictionary entries it has found in which “trouble” is or forms part of the entry’s English gloss.

The Nawat items are in the column on the left. Some are repeated because, as I’ve explained, it’s looking in more than one dictionary at once. Also, Since I specified in my search that the character string “trouble” only needed to be part of the word found, some of the results actually have the form “troubled”, which is fine since I’m interested in those entries too.

So I look over the list of Nawat equivalents and think: hmm, I’d like some more information about that last word, yulkakasiwi. So I click on that word and am given a choice of which data I would like to see. Say I choose Campbell’s dictionary (usually a good choice!), then up pops Campbell’s entry for yulkakasiwi over here on the left. Of course we had to manipulate Campbell’s original text to sort the data into fields and did a small amount of re-encoding to bring it and the other sources into line. For instance, this capital Q here is NawaCoLex’s code for Cuisnahuat dialect.

And this other entry in the bottom left corner is the corpus wordlist entry for the word yulkakasiwi. Because this system houses lexicons and corpus together, that information is accessed as easily as the dictionaries and in exactly the same way. This wordlist is generated by the software from the text corpus and what it does is count the occurrences of the word form in the whole current corpus and list all references. As you can see there is just one occurrence, and “NPT01_53.018” tells both me and Toolbox where that occurrence is located in the texts. A single click on it opens a text window where the part of the corpus containing the referenced item is found. That’s the big window that is taking up most of the lower half. You can see the matching line reference there: “NPT01_53.018”. Here, we’ll highlight the word yulkakasiwi so that our readers will be able to spot where that is.

NBTN: So you not only obtain the lexical data reported by Campbell but simultaneously see all the real examples of it in your corpus. From that combination of information I imagine you can tell a lot about how the word is really used by Nawat speakers.

Alan: Let’s say that if such information is available to us anywhere, then I can probably see it here. So at the very least it serves to tell me what we know right now about it. But coupling corpus data with dictionary information is far superior to having to rely exclusively on the latter. The corpus tells us lots of things. Even this single occurrence is enough to confirm this word’s existence, its meaning, and speakers’ knowledge of the word. Knowing how frequently the word occurs in our texts is itself interesting information related to use. Furthermore, because we know which town each corpus text comes from, we can see here where the word was used. Now I see something quite interesting here: I know that the speaker in this particular text was from Izalco, whereas Campbell, working in a different region, has documented the word in Cuisnahuat, which is nowhere near Izalco of course. That’s good because now we know that yulkakasiwi was not restricted to one particular place, as some words sometimes are; we can conclude that it has a rather wide geographical distribution. That knowledge is not provided either by the dictionary entry alone or by the corpus datum alone, but only by the combination of both, which NawaCoLex has brought to our attention in this instance.

NBTN: We started by looking up an English word just now. You could probably start from a Nawat word too?

NBTN: We started by looking up an English word just now. You could probably start from a Nawat word too?

Alan: Yes, and there’s also a further option with Nawat words, which is to use the Wordfinder here in the top left corner rather than doing a concordance search. The results are similar but not identical. I can just type in a word here such as kechkuyu which means “neck”, then right-click. Again, if there were only one entry for kechkuyu it would simply appear directly in the window underneath, but unsurprisingly it has found three entries from three different dictionary components, so it first gives us this Multiple Matches list which you can see popping up over on the right. That is so that we can choose which of the three entries we wish to display. The second column there gives the Spanish glosses in each entry (I can choose to be shown Spanish or English glosses, but it’s set to Spanish now): two sources gloss it as “cuello” and one as “pescuezo”. The right-hand column is to tell us which sources they are. Sometimes this information is sufficient for what I need to know. If not, I can click on one of the options and view that dictionary entry in full.

NBTN: What three sources are they?

Alan: The first entry it found was in the old NawatLex database. The second is Campbell’s dictionary, and the third component listed is the Léxico Básico Náhuat, a corpus-based elementary Nawat dictionary that I am developing. There, let’s display the Léxico Básico Náhuat entry for kechkuyu. It displays back here on the left.

So much for dictionaries, but there is one other step in the translation process that I still have to show you: as you can see it is also in Toolbox. Observe the chapter-and-verse markers in purple first, such as the one that says “MAT18.007” on the seventh line of the biggest window here. The rest of the window is filled with alternating green and black lines. On the green lines we find the Greek text of each verse, with each Greek word followed by some numbers and some Roman capitals. These show the Strong’s Number and the grammatical features of the preceding Greek word, just as we saw in one of the e-Sword displays; in fact, that is where these lines of text were copied from.

So much for dictionaries, but there is one other step in the translation process that I still have to show you: as you can see it is also in Toolbox. Observe the chapter-and-verse markers in purple first, such as the one that says “MAT18.007” on the seventh line of the biggest window here. The rest of the window is filled with alternating green and black lines. On the green lines we find the Greek text of each verse, with each Greek word followed by some numbers and some Roman capitals. These show the Strong’s Number and the grammatical features of the preceding Greek word, just as we saw in one of the e-Sword displays; in fact, that is where these lines of text were copied from.

NBTN: The black lines look like an interlinear Nawat translation!

Alan: Basically that is what they are. Underneath each item in green is either a Nawat gloss for the Greek word or a grammatical function indicator such as DS for “dative singular”, GP for “genitive plural”, AorActInf for “aorist active infinitive” and so on. Greek finite verbs are fully glossed directly into Nawat, e.g. witz/ajsi (meaning “witz or ajsi“) at the end of verse 7, shiktzinkutuna in the third line of verse 8, etc. We might call it a word-by-word translation, covering every single word in the Biblical text, right the way down to definite articles (ne in Nawat).

NBTN: That’s brilliant!

Alan: Well now, hold your horses! Before you get too excited about this, although “word-by-word” might sound like a good thing to lay people, I am emphasising that as a warning about what this is not: it is not a good Nawat translation. A lot of the time, the Nawat lines would not even make sense as they stand, but that doesn’t matter too much because they’re not supposed to. They merely indicate roughly the Nawat translation of each Greek word individually.

NBTN: Right, I follow you. So, the green lines are copied and pasted from e-Sword. Who puts in the black lines then?

Alan: Well the trick is getting Toolbox to do it of course, but it’s actually easier than you would probably think. First of all Toolbox reads the green line, picking out the items to translate. Actually the way I have this set up, it ignores the Greek completely (that’s only there for me to see) and only looks at the Strong’s Numbers and the grammatical codes. Toolbox has its own dictionary which “translates” each of those items into a Nawat word (or a grammatical indicator like DS). You can see a sample entry in its dictionary in the middle window at the bottom of the screen: so it will translate “3759 INJ” to “ay!”.

In a separate operation we can generate a complete concordance of the original text in terms of Strong’s Numbers. In the bottom right corner you can see an example of the concordance for item 3759.

NBTN: So Toolbox gets the word glosses from the dictionary and generates the interlinear document from that. Who puts the words in the dictionary though?

Alan: I do.

NBTN: How many dictionary entries are there?

Alan: So far, about 3,000 lexical items (i.e. Strong’s Numbers). Additionally there are over 2,000 Greek finite verb forms. Entering the words is itself a semi-automated process where Toolbox prompts me to provide a Nawat gloss and I just have to type it in; the programme does the rest and keeps it all in order.

I didn’t set this up until I had already translated and revised one whole gospel book. I pasted in the chapters in the Greek-plus-Strong’s notation, leaving the black lines empty at first. Then I let Toolbox have a go at translating it. At this point the dictionary was empty, so of course Toolbox dutifully reads through the first verse of chapter one and lets me know that it has failed to find any of the words. Now as I click on the words one-by-one Toolbox asks me how to gloss each one. As I provide a Nawat gloss, that goes into Toolbox’s dictionary so that it will never ask me to gloss that word again. Since I had already translated Luke, what I was actually doing here was telling Toolbox what Nawat word I had already chosen in the translating process as the equivalent to each Greek word. Surprisingly soon, Toolbox gets quite good at glossing whole new lines of text, only stopping to “ask” for the new vocabulary items. It took about a week to work through the book of Luke like that. From there on, the system is primed with a pretty good basic vocabulary and will mostly need my “help” with more “difficult” words that come up in future.

Next I reread my Luke translation keeping an eye on the interlinear glosses to see how they compared. Now because of the limitations of the glossing approach, most of the differences found between the interlinear gloss and the “real” translation are necessary differences. There are dozens of good reasons why they should differ, and to explain them all would be to write a book on the art of translation. But every so often, the differences found were in fact cases of my not having been consistent enough, problems of “human fallibility” if you like.

NBTN: Did you repeat the same procedure for the other books you’ve translated?

Alan: No. Once the system had been primed based on one book, I went into a second phase with a different methodology. Now that Toolbox already knew most of the words most commonly encountered in these texts, from there on I reversed the order, letting Toolbox have a try first and warn me about new words coming up in the next chapter before I tried to translate it. Giving Toolbox those glosses amounted to preparing the vocabulary ahead of actual translation. Remember only the words I have never translated before require attention because Toolbox “remembers” the others, and believe me, it has a better memory than I have.

An experienced translator will try only to have to look up each difficult word in a text once and to translate it consistently if the word recurs in the same text. That’s not too hard if the text is short, but beyond a certain length it becomes harder to keep track of all the words and expressions, which may result both in wasting time by looking up a word you’ve already looked up once, and in a loss of consistency in the final result. So the longer the text the harder the translator has to work to keep tabs on all these things, unless the computer can be coaxed into helping out.

NBTN: Well that has given us an idea of at least some aspects of the general mechanics of what goes on inside the Ne Bibliaj Tik Nawat “translation laboratory”, although I realise you have simplified a lot of the details to help us grasp the overall picture. I’d like to ask you two final questions. Do you think this method would be found useful by others doing similar kinds of translation work? And do you consider that your methodology is now perfected?

Alan: The quick answers would be yes to the first question and no to the second.

Let me repeat that some parts of what I’m doing were already out there; all I did was recognise their value for my own work and integrate them into my work system. Other parts were not ready-made and I had to be a bit more creative. Certainly I’d be pleased to be able to share the knowledge I’ve acquired in the process and the essential concepts of the work flow I have developed with anyone else facing a similar challenge.

I’m quite sure this method will continue to evolve, and I’m already aware of some ways it might be improved in the future. That is fine but there is also work to be done, and my main job right now is to get on with this translation. Come back some other time and I’ll tell you about all the things I’ve changed by then, and also about the new challenges that will no doubt still lie ahead.